The Demise of Australia’s Snow Gums

Whatever idealised Australian landscape comes to mind, eucalyptus trees (gum trees) are likely to be part of that vision. This is not surprising as eucalypts make up the most common forest types across Australia, with over 127 million hectares of eucalypt forest from a total of 162 million hectares of native forest.

There are over 900 eucalypt species native to Australia1. As an ancient continent, there has been time for populations to have evolved into very specific niches, which can make taxonomy difficult. In some cases, species consist of only a small number of trees in populations occupying specific or isolated niches, and as the climate changes, these species become very vulnerable. This makes conservation of this biodiversity very important.

Bogong High Plains at sunset

Snow Gums are the classic alpine tree of Australia’s cooler areas, generally growing at heights between 1,300 and 1,800 metres above sea level, although they can be found as low as 700 metres in cool locations. They are particularly known along the alpine areas of Victoria and New South Wales and are a highlight of any visit to the Australian High Country.

Eucalyptus pauciflora is the most common species and there are 5 sub-species2. It is a mallee type tree that typically grows to a height of 20–30 m and forms a lignotuber. The species regenerates from seed, by shoots below the bark, and from its lignotuber. It is the most cold-tolerant species of eucalypt, with an ability to survive temperatures down to −23 °C and year-round frosts.

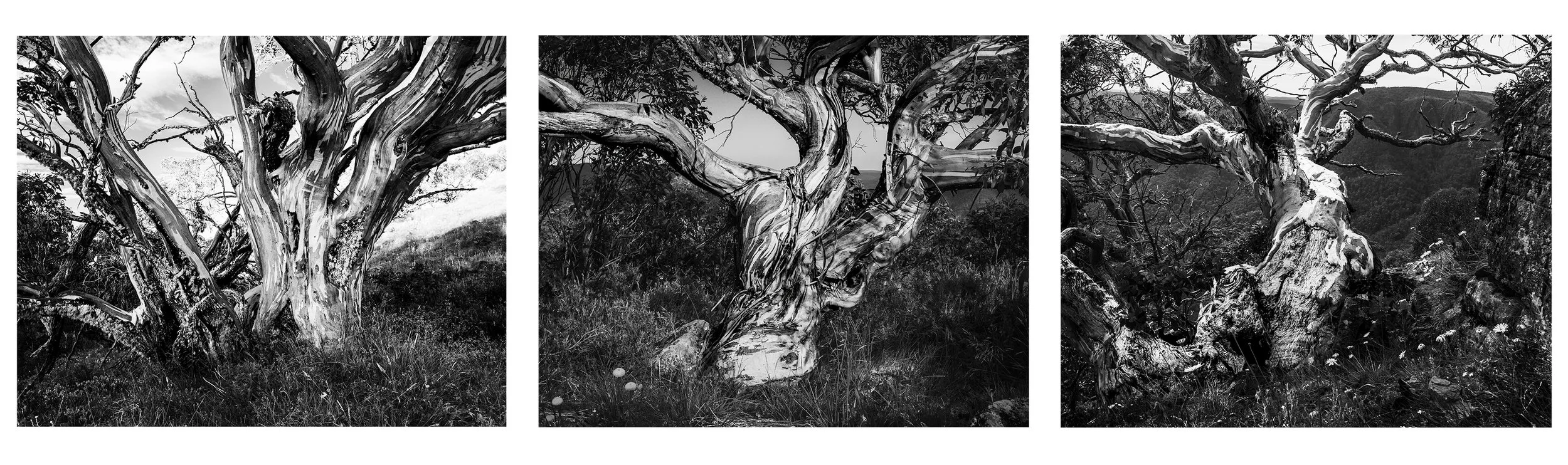

A very old Snow Gum

On the Mount Buffalo plateau, one of my favourite places in the alps, another snow gum species occurs, E. mitchelliana, the Mount Buffalo gum, which occurs only along the northern and north-eastern plateau rim, and at the Back Wall south of the Horn. There is also E. coccifera, the Tasmanian snow gum, E. lacrimans, the Weeping Snow Gum, and E. gregsoniana, the Wolgan Snow Gum.

The mountainous regions of Australia have always been subject to periodic bushfires. The bark on the stems of snow gums is particularly thin and their trunks and branches are frequently killed outright by fire. However, the lignotuber allows snow gums to vigorously re-sprout after fire, rapidly producing new leaves.

This is why snow gums often have multiple trucks with brightly coloured bark spreading from their bulbous base. As a photographer, these multiple trunks can make finding a composition difficult and the temptation (aka sensible strategy) is to move in closer to capture the wonderful colours in the bark and leaves3.

Snow Gums on the Baw Baw plateau

The image of the stockman in this mountain landscape holds a special place in the myths of the development of modern Australia since colonisation. As Clancy of the Overflow says in Banjo Paterson’s The Man from Snowy River:

"He hails from Snowy River, up by Kosciusko's side,

Where the hills are twice as steep and twice as rough,

Where a horse's hoofs strike firelight from the flint stones every stride,

The man that holds his own is good enough.

And the Snowy River riders on the mountains make their home,

Where the river runs those giant hills between;

I have seen full many horsemen since I first commenced to roam,

But nowhere yet such horsemen have I seen."

This landscape feels so precious to many Australians. The old and rounded mountain tops above the tree line, with high plain grasslands full of wildflowers in summer and snow covered in winter, surrounded by patches of woodland filled with snow gums and shrubs. The views from escarpments of eroded sedimentary rock of ancient seabeds overlooking repeating ridge lines fading through the blue eucalytus haze. The deep, treacherous gullys between spurs full of tall gum trees, thick scrub and loose rock.

Craig’s hut - built in 1982 for the film 'The Man From Snowy River' and rebuilt after the 2006 Great Divide Fire

Australia’s alpine area is relatively small – covering about 11,000 square kilometres or 0.15 per cent of the continent – but have outstanding natural value and are home to unique and endangered plants and animals such as the mountain pygmy possum and bogong moths.

It is common to refer to these landscapes and species such as snow gums as being under threat or at risk, as if the event is yet to happen. This is not true; they are already being devastated. Too much climate change reporting confuses tenses as if these impacts will be in the future. Stories refer to potential extinctions, ignoring the extinction crisis we are already in. In fact, these risks have already been realised with more impacts locked in, even under the most optimistic of scenarios. I can’t help feeling that these iconic snow gum woodlands are already ‘dead men walking’.

In recent decades, wildfire has been devastating huge areas of the snow gum forests, with significant fires in the Victorian High Country in 1998, 2002-03, 2006-07, 2013 and 2019-20. Only 0.5 per cent of Victoria’s snow gum forests along the Great Dividing Range have remained unburnt since 1938, and 92 per cent have been burnt at least once since 2000. 30 per cent have been burnt three, four or five (or more) times since 1938.

The problem is that, while snow gums are well adapted to fire and can respond to a fire event, repeated fires see the number of new sprouts emerging from the lignotuber decline markedly. Repeated fires also see the loss of new seedlings as the seedbank is diminished.

Almost everywhere you go in Victoria’s high country, ridgeline after ridgeline has the white pale of dead tree trunks, either snow gums or its lower elevation neighbour Alpine Ash. Long-unburnt, old snow gum forests now comprise only one percent of snow gum forests in across Victoria.

View from Lake Mountain

In addition to increased frequency of fire, snow gums are under attack from the native wood-boring longicorn beetles. The longicorn larvae feed on the outer wood and inner bark of affected trees until the bark is completely removed. This will kill the tree, and in severe outbreaks, result in the death of entire communities of trees.

The scale of this dieback is unprecedented and although climate change (warmer weather and drought stress) is suspected to be part of the problem, currently the causes are not well understood.

The loss of snow gums has other impacts, including an increased grassy understory instead of structurally complex shrubs, which reduces habitat for rare and endangered animals, reduced carbon sequestration, and changed water flows as a result of reduced snow retention.

Incoming rain over Bogong High Plains

There is a school of thought that pessimistic reporting will turn people off taking action on climate change, that people will give up. This may be true, but I don’t see how denial of the situation will help. In fact, a cool-headed assessment of the future offers two opportunities to adapt to the reality of rapid, anthropogenic climate collapse.

Firstly, while certain environmental niches may become less widespread, like Australia’s cool alpine climates, there may be areas that can be protected. Increasingly, fire fighting plans need to be put in place to protect environmental assets such as remnant areas that have remained relatively unburnt. This occurred in the 2019-20 Black Summer fires with the protection of the Wollemi Pine and needs to be in place in Victoria’s fire planning.

Secondly, more proactive management of the land will be required. How to best manage forests to minimise bushfire risk is contentious but certainly reducing human causes of fires will help, for example, by reducing 4WD traffic and enforcing stove only areas. There are also ways to manage forests to encourage certain species post fire.

Sunset near Lake Mountain

There is increasing recognition of the impacts of climate change on Victoria’s High Country. Academic research is being undertaken, environmental group are lobbying and supporting local action4, and the media are picking up these stories.

Government has also taken some action. After the 2013 Harrietville-Alpine Bushfire, the Victorian Government initiated a rapid response forest recovery program, which aimed to restore Alpine Ash forests that had been burnt and where only limited numbers of parent trees had survived. Since then, the program has been expanded considerably as more areas have been burnt multiple times. As part of the recovery from the 2019-20 Black Summer fires, $7.7 million was committed to collect and airlift Alpine Ash seeds to allow for resowing of burnt areas. This was part of a $54.5 million Bushfire Biodiversity Response and Recovery program. But this is only the start of the costs of adaptation.

Adaptation does not mean we should lessen efforts for widespread local and global mitigation of climate change. We should continue to seek to minimise any increase in temperature because – while some ecologic niches at the edge may already be lost, there are others that are moving closer to the edge and can still be saved.

Almost every view from the High Country shows the scars of the increasing frequency and extent of fire. These woodlands will not recover in my lifetime, perhaps never. As a photographer I feel compelled to capture images of the landscapes that are at risk and those that are already destined to be lost. It is a small contribution but can help to raise awareness and focus attention on local action that can be undertaken right now, even while global action remains insanely slow.

I can only hope that the value of these photos will not be mostly in the future, like old photos that show us a bygone era that we look at with a sense of nostalgia and regret.